Why is the global economy hamstrung by heavy debts and weak banks? Or put another way, why doesn't deleveraging happen, and the weight of debt reduce, and why doesn't the economy expand so the weak banks can once more become robust and healthy ones?

Short answer, it's the demand side stupid! The longer version was offered by Paul Krugman when he asked the ironic question, "To which planet are we all going to export?" Basically the demand needs to come from somewhere - unless of course you believe that "supply creates its own demand". What makes this crisis different from many of its predecessors is the global extension of the problem. If we were just talking about a few countries (as in the Asian crisis of 1998, which is so often mentioned in this context) then the answer would not be that hard, reduce currency values and export like mad to the non-affected countries. But in the current crisis, almost all developed economies are affected to one degree or another. The to one degree or another part is interesting, but it doesn't form part of what I am driving at here.

There are countries which are not so heavily in debt, and which do have a large growth capacity and a huge quantity of so called "pent up" demand - the so called Emerging Economies. But the simple math fails us. If we look at the first chart below the non "advanced" economies have been growing much more rapidly than the advanced ones since around 2002, so the potential is there.

But if we look at the second chart, these economies are still only around 40% of global GDP, so it is demand in 40% which is having to pull the other 60% with it. The interesting part is that in the space of a decade these economies have surged from 20% to 40% of the total. If the same trend continues by 2020 they could easily constitute 60%. Then things could be different, since we could have 40% of the total living from exporting to the other, faster growing, 60%. But we aren't there yet, which is why I think this decade will be a transitional one, one during which the developed economies (on aggregate) will struggle to find growth.

Nonetheless, emerging markets are growing fast, aided from time to time by an injection of liquidity from the developed world central banks. The IMF still expects the world economy to grow by 3.5% this year. Two issues cast something of a shadow over the immediate outlook. The first is the visible slowdown in Chinese growth, and the other is ongoing concern about the ultimate endpoint of the Eurozone drama in innumerable acts. The key point to appreciate about the second issue is that with “risk off” due to the European Debt Crisis, even the Emerging Markets are unable to exploit their huge potential for growth. Capital is not flowing into these markets in the way it did following the various rounds of QE in the US and even the LTROs in Europe. These impacts can be seen in the JP Morgan Global Composite PMI chart below.

Both QE1 and QE2 were followed by large surges in global activity, and even last November's LTRO from the ECB produced an unexpected turnaround that some would argue has only been putting off the inevitable. Certainly, the force of the LTRO impact wrong footed many of us, since it produced a stabilization of global activity which lasted all through the first half of this year (see the latest German GDP results for additional evidence).

The China factor is also important. It was curious to watch a world which had just slumped following the collapse of an unsustainable debt orgy hoping to save itself by egging another country on to repeat the performance. Naturally, history isn't a mere repetition of the same, and the Chinese conundrum contains plot elements not seen elsewhere, including an ultra important export sector, but still it is hard to see how so many people could have remained silent in the face of what appears to have been a crazed investment boom. Still, China is a long way from having its back broken, even if the spinal column does need a lot of straightening out. The awkward part is that the "Chinese correction" comes just at the wrong time as far as global growth is concerned.

In any event, the BRIC concept was always far too general. It is just based on population size and the presence of underdevelopment. The key factor for growth dynamics, as I keep arguing, is age structure, and in this sense India and Brazil look very different from Russia and China. Economic growth is partly about favourable demographics, and partly about institutional quality. Some EMs have favourable demographics, and some of these also are increasingly moving towards growth enhancing institutions. Others with favourable demographics are an institutional nightmare - Argentina is a good example, and others (like Ukraine or Belarus) have neither favourable demography nor positively evolving institutions, indeed in the two aforementioned cases it is unlikely they ever will.

What follows is a summary of my July manufacturing PMI report. The complete version can be found on Slideshare (here).

Manufacturing Visibly Slowing Across The Planet

We live in a globalised world. And what better illustration of this truism than the way in which manufacturing activity is steadily slowing across the planet. In theory the worsening conditions are a by-product of the Euro Debt Crisis, but in reality there are a multitude of factors at work – the slowdown in China, exhaustion of a credit boom in Brazil, a Japan which can’t export as much as it needs to due to the high value of the Yen, a United States where the various rounds of quantitative easing appear to have run out of steam.

But we also live in a world which is structurally in transition. The developed countries are overly in debt (especially when we consider health and pension liabilities looking forward) and ageing excessively. The emerging economies are experiencing a massive demographic, cultural and economic transition. The so called “Arab Spring” is just one example of this. Risk is being re evaluated, with developed world risk rising, at the same time as risk perception of Emerging Economies improves.

So the paths are crossing. Recessions in the developed world will now be more frequent and the recoveries shallower, while EMs will experience substantial catch up growth, while the recessions will be much more modest than previously.

Having said this, it is still impressive to note the diversity even among the EMs. This month I was struck by the way manufacturing sectors in some countries (like Indonesia and Vietnam) are now evidently having a hard time of it, while in others (India, Turkey) they are managing to keep their heads just above water. But in all cases what is most notable in the report summaries that follow is the way in which exports are suffering, and export order books contracting, which suggests we have another six months or so of stagnation or worse staring us in the face.

Global manufacturing downturn gathers pace in July

The global manufacturing sector slid further into contraction territory at the start of the third quarter. At 48.4 in July, the JPMorgan Global Manufacturing PMI posted its lowest level since June 2009. The PMI remained below the neutral 50.0 mark for the second straight month, signalling back-to-back contractions for the first time since mid-2009.

Europe remained the main source of weakness during July, while the performances of the US, Brazil and much of Asia were at best only sluggish. Manufacturing PMIs for the Eurozone and the UK sank to their lowest levels for over three years. Within the euro area, the big-four nations fell deeper into recession, while Greece continued to contract at a substantial pace. Eastern Europe fared little better, with downturns continuing in Poland and the Czech Republic.

The ISM US PMI posted a sub-50.0 reading for the second successive month in July. Rates of contraction accelerated in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam, but eased slightly in Brazil and China. Brighter spots were Canada, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Mexico, Russia and South Africa, which all signalled expansion during the latest survey period. Manufacturing production and new orders both fell for the second month running in July, with rates of contraction gathering pace. International trade volumes, meanwhile, declined to the greatest extent since April 2009. Job losses were reported for the first time November 2009. With demand still weak and a sharp drop in backlogs suggesting spare capacity is still available, staffing levels could fall further in coming months.

Commenting on the PMI survey, David Hensley, Director of Global Economics Coordination at JPMorgan, said:

"Weak demand and the ongoing period of inventory adjustment pushed the global manufacturing sector into deeper contraction at the start of Q3 2012. Job losses were also recorded for the first time in over two-and-a-half years. Recent cost reductions are providing some respite, but this will be of little long-term benefit if underlying demand fails to pick up.”Asia

Viewed as a continent, it is very hard to make generalitzacions about Asia. Japan is among the oldest countries on the planet. Domestic demand is congenitally weak, and exports struggle against the weight of an overvalued yen. The important point to notice is that all last years predictions about Tsunami reconstruction bring a new lease of life to the country have proven to be ill founded. All the associated damage has done is produce more debt. And still the economy struggles to grow. This issue will doubtless become worse after the government introduces the long promised increase in consumption tax.

China is suffering from a real estate adjustment which influences internal demand, while the global trade slowdown harms the export sector. In addition, the country’s potential growth rate, after hitting double digits at one point, is now slowing steadily as China steadily moves from emerging economy to mature economy status. India continues to advance at rates which are not seen in most Asian economies these days, but the country has an endemic inflation problem which remains unresolved, and growth is also hampered by poor infrastructure and widespread corruption. The semi developed economies like South Korea and Singapore still struggle to overcome weak export demand, and even new emergers like Vietnam and Indonesia remain challenged to find growth at this point.

Japan

The Japanese economy slowed more sharply than expected in the April-June quarter as exports and consumer spending lost steam, raising the specter of further deceleration for the rest of this year. Japan's economy grew strongly in the first quarter on increased government spending to aid in the rebuilding of areas battered by the March 2011 earthquake and incentives to boost sales of fuel-efficient vehicles. But fiscal policy appears no longer enough to offset the growing impact of the high yen coupled with Europe's persistent debt crisis and the resulting global slowdown on Japan's export-reliant economy.

July data from the Markit/JMMA manufacturing PMI survey confirmed the continuation of the April-June trend since it showed manufacturing output falling at the sharpest rate in 15 months, with both new orders and new export business decreasing at accelerated rates.

Commenting on the Japanese Manufacturing PMI survey data, Alex Hamilton, economist at Markit and author of the report said:China

“Business conditions in Japan’s manufacturing sector took a turn for the worse in July, according to latest PMI survey findings. Factory output, new orders and exports all decreased at the fastest rates since April 2011, while input buying and backlogs also decreased markedly. These are worrying developments given the weakness of global demand at present.

In China the HSBC Purchasing Managers’ Index posted 49.3 in July, up from 48.2 in June, signalling Chinese manufacturing sector operating conditions only deteriorated marginally. Indeed, the month-on-month increase in the index, though small, was the largest in 21 months.

So while the Chinese economy is holding up far better than most of the hard landing people thought, the expectation was that it would be doing more than just holding up at this point in time. It was supposed to be both in the midst of a full-fledged recovery and driving the global demand chain. Chinese economic growth slowed to an annualised 7.6 per cent in the second quarter, its slowest pace since the height of the global financial crisis in 2009. And further data published last week indicated that it may need to do more to stop the rot which has now set in. Industrial production growth dipped to 9.2 per cent from 9.5 per cent in June, defying many analysts expectations for a rebound. Retail sales growth fell to 13.1 per cent from 13.7 per cent, while investment only managed to hold steady at a 20.4 per cent year-to-date pace. These are still large numbers, but for China, incredibly, they represent a slowdown. The fear is there may be worse to come.

Commenting on the China Manufacturing PMI™ survey, Hongbin Qu, Chief Economist, China & Co-Head of Asian Economic Research at HSBC said:

“Final manufacturing PMI confirmed only a modest improvement of manufacturing conditions thanks to the initial effect of the earlier easing measures. But this is far from inspiring, as China’s growth slowdown has not been reversed meaningfully and downside pressures persist with external markets continuing to deteriorate. We still expect Beijing to step up policy easing in the coming months to support growth and employment.”

India

In India the HSBC Purchasing Managers’ Index posted 52.9 in July, down from the reading of 55.0 recorded in June and pointing to a continuing slowdown in the manufacturing sector. In fact Indian industrial production slid in June for the third time in four months, with output of capital goods plunging the most on record. Production at factories, utilities and mines declined 1.8 percent from a year earlier, after a revised 2.5 percent rise in May. Capital goods output, an indication of investment in plants and machinery, fell 27.9 percent.

Indian manufacturing has been struggling in recent months as inflation hovering above 7 percent has been eating into domestic demand and Europe’s debt crisis restricts exports. Price pressures from a drop in the rupee and the impact of a weak monsoon on crops forced the central bank to leave interest rates unchanged in July, breaking a trend towards reduced borrowing costs which extends from China to Brazil to Europe. The rupee has now slumped about 18 percent against the dollar in the past 12 month.

Headline inflation, which was 7.25 percent in June (the fastest pace among the world’s largest emerging markets) fell unexpectedly to the slowest pace in nearly three years in July following a sharp drop in fuel prices, but risks of a revival in price pressures may still discourage the central bank from lowering interest rates to spur economic growth. The wholesale price index rose 6.87% in July from a year earlier.

Indian GDP rose 5.3 percent in the first quarter from a year earlier, the slowest pace since 2003, and both Standard & Poor’s and Fitch Ratings have warned they may strip the country of its investment- grade credit rating, citing risks including fiscal and current- account deficits.

Commenting on the India Manufacturing PMI™ survey, Leif Eskesen, Chief Economist for India & ASEAN at HSBC said:

"Manufacturing activity grew at a slower clip in July on the back of power outages and a moderation in new order inflows, with the weak global economic conditions dragging down export orders. Moreover, orders decelerated faster than inventory accumulation suggesting that the more moderate expansion in output will continue in the months ahead. The slowdown in order growth allowed manufacturers to reduce backlogs of work. Moreover, input and output prices decelerated, but inflation remains above historical averages."

Europe Heads Into Its Next Recession

The eurozone economy shrank in the second quarter, having flatlined in the first, despite continued German growth which looks increasingly fragile with every passing day out. Bailed-out Portugal saw its recession deepening with GDP diving by 1.2 percent on the quarter and 3.3% on the year, meaning that the threat of missing its deficit target this year is becoming increasingly real.

Figures released earlier had already showed deficit-cutting measures helped to shrink Greece's economy 6.2 percent year-on-year in the second quarter. Italian data last week showed the economy contracted 0.7 percent quarter-on-quarter, compounding the difficulties for Mario Monti's technocrat government as it tries to avoid a bailout. Spain's economy shrank 0.4 percent over the same period, pushing it deeper into recession.

As a result the currency bloc contracted by a quarterly 0.2 percent despite Germany eking out 0.3 percent growth. The storm cloud don't cease to gather, though, and just today the forward-looking ZEW sentiment index slid for a fourth month running. All the leading indicators for Germany now suggest looming contraction.

Thus, even as Europe’s leaders continue to fiddle around with the debt crisis, the economies of the Euro Area sink deeper into the mire. The latest round of PMIs suggest that the recession will become official in the third quarter, and at the present time there is no let up in sight.

Certainly progress is being made in terms of the liquidity and capital needs of Euro Area banks, and further moves to ease sovereign financing difficulties seem to be at hand, But competitiveness issues are still a long way from finding solution. There is no evidence to back the idea of a surge in German inflation, while VAT hikes in country’s like Spain continue to damage their relative cost position.

The ECB has raised market expectations considerably in recent days. In the short run such expectations have foundered on disappointment. In the longer run, however, the ECB is likely to have few unbreachable limits to its freedom of action. Movement by the EU and the ECB will require formal requests for aid and involve conditionality. When this happens the most likely policy move with be SMP reactivation by the ECB in the secondary market and EFSF purchases in the primary one. Finally a reminder: it is important to remember the Greek problem has not gone away, it is simply in limbo. The Troika have gone home for now, but they did leave a message, courtesy of the Ramones, “see you in September”.

Eurozone manufacturing recession deepens at start of third quarter

The final Markit Eurozone Manufacturing PMI fell to a 37-month low of 44.0, down from 45.1 in June. The PMI has now signalled contraction for 12 consecutive months. Widespread weakness was seen across the region, with almost all of the national PMIs at sub-50.0 levels. Only Ireland bucked the trend, seeing improved business conditions as its PMI hit a 15-month high. Rates of decline in Germany, France and Spain were either at or close to the steepest since mid-2009. Italy recorded the worst overall performance in three months, while Austria slipped back into contraction and business conditions in the Netherlands continued to deteriorate. Greece stayed rooted to the bottom of the PMI league table.

Casting a long shadow over the future, total new orders contracted for the fourteenth straight month, with the rate of decline the third-fastest for over three years. Greece and Spain recorded the steepest falls, while the big-three of Germany, France and Italy all posted sharp contractions. Declines in the Netherlands and Austria were much weaker in comparison, while Ireland saw new order growth hit a 15-month high. New export orders fell at the fastest pace for eight months, with intra-Eurozone trade particularly subdued. Only Ireland and the Netherlands reported increases in new exports. The German export machine remained firmly in reverse during July, recording the steepest drop in new orders of all countries and the fastest rate of decline since May 2009.

Chris Williamson, Chief Economist at Markit said:

“The Eurozone manufacturing sector’s woes intensified again in July. Output fell at the fastest rate since mid-2009, consistent with the official measure of production falling at a quarterly rate in excess of 1%. Manufacturing therefore looks to be on course to act as a major drag on economic growth in the third quarter, as the Eurozone faces a deepening slide back into recession.

Germany

The performance of the German manufacturing sector took another turn for the worse in July, with output and new orders both declining at the sharpest rates since April 2009. This led to a further drop in the Markit/BME Germany Purchasing Managers’ Index from 45.0 to 43.0 in July, its lowest level since June 2009.

July data also saw the thirteenth successive monthly contraction of incoming new business in the German manufacturing sector. This is the longest continuous period of falling new orders since the survey began in April 1996. Survey respondents frequently reorted an unwillingness among clients to commit to new spending, largely in response to the uncertain global economic outlook. New export work continued to decline at a steeper pace than total new business receipts in July. Manufacturers noted shrinking sales in Western Europe, alongside softer demand in Asia and the US. The overall decline in new export work was the steepest since May 2009.

Commenting on the final Markit/BME Germany Manufacturing PMI® survey data, Tim Moore, senior economist at Markit and author of the report said:

The German manufacturing PMI number slipped to bronze position in the ranking of the ‘big four’ eurozone economies during July, its lowest position for three years and indicative of a sharp deterioration in business conditions over the month. Manufacturers linked the latest setback to shrinking export sales and a general shortage of new work to replace completed projects. Output dropped at the steepest pace for over three years and job shedding was the most marked since the start of 2010.

Italy

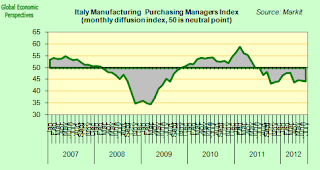

Manufacturers in Italy continued to face a challenging operating environment at the start of the third quarter. A further contraction in demand led to lower output levels and the sharpest reduction in employment for 33 months, with a sharp and accelerated decrease in backlogs of work underlining the degree of excess capacity in the sector.

The Markit/ADACI Purchasing Managers’ Index dipped to a three month low of 44.3 in July, down from June’s reading of 44.6. The headline index has posted below the neutral mark of 50.0 throughout the past year, and was below the average recorded over the second quarter as a whole giving the impression that the recession may even be deepening.

Phil Smith, economist at Markit and author of the Italian Manufacturing PMI said:

“July saw the recession in the Italian manufacturing sector extend to a year. Moreover, the downturn was shown to have deepened as the PMI sank to its lowest level in three months, primarily reflecting a sharper reduction in staffing levels. A solid and accelerated decrease in stocks of purchases also dragged the headline index lower, and suggested that firms had grown more concerned about cash flow and were not anticipating a rise in production requirements in the near term.

Central and Eastern Europe

Czech manufacturing business conditions deteriorate further

The latest HSBC PMI report confirmed the ongoing weak downturn in the Czech manufacturing economy at the start of the third quarter. New orders and purchases of inputs by manufacturers both fell for the fourth successive month, while output remained stagnant. This is all in line with the fact that Czech GDP has now been falling for three successive quarters. The PMI remained below the no-change mark of 50.0 in July, continuing the pattern seen since April. The deterioration in overall business conditions signalled by the headline figure remained modest, however, as the PMI was little-changed at 49.5 from June’s 49.4.

Commenting on the Czech Republic Manufacturing PMI survey, Agata Urbanska, Economist, Central & Eastern Europe at HSBC, said:Contraction of Polish manufacturing sector slows in July

“The PMI index changed little in July compared to June and still points to a slight deterioration of business conditions in the manufacturing sector. Among the index components, the suppliers’ delivery times improved (lengthened), offsetting worsening output, new orders and employment indices. We assess this combination as negative and remain cautious of downside risks. This is particularly the case in face of weaker than expected leading indicators in July like IFO and PMI in Germany. The PMI’s input and output prices indices show a further decline of inflationary pressures, and leave room for the central bank to cut its policy rate to a new record low later this year.”

HSBC survey data compiled by Markit indicated a near-stabilisation of business conditions facing Polish manufacturers in July. New orders declined at the weakest rate since March, while output fell only marginally since June and firms raised headcounts at the fastest rate since February 2011. The PMI recovered from June’s 35-month low of 48.0, posting 49.7 in July. That signalled a fourth successive overall deterioration in the business climate, but at only a marginal pace that was the weakest in that sequence.

Commenting on the Poland Manufacturing PMI® survey, Agata Urbanska, Economist, Central & Eastern Europe at HSBC, said: “The recovery of the PMI index, despite the fact that it still remains in contraction territory, is a positive following a month of activity data releases all surprising on the downside. The PMI still points to a marginal deterioration in business conditions in the manufacturing sector, but the pace of deterioration has slowed compared to previous months.

Turkish manufacturing output falls for first time in four months

The seasonally adjusted HSBC Turkey Manufacturing PMI dropped below the 50.0 no-change mark in July, posting 49.4. This followed a reading of 51.4 in June and signalled the first deterioration in business conditions since March. That said, the decline was only marginal. Both output and new orders decreased in July. New business fell for the fourth month in 2012 so far, following stagnation in June.

Commenting on the Turkey Manufacturing PMI® survey, Melis Metiner, Economist at HSBC, said:United States

“Turkish manufacturing conditions deteriorated in July, falling into contraction territory for the first time since March. Both output and new orders fell, while new export orders recovered after a sharp decline in June. The pace of improvement was marginal, however.

US PMI indicates slowest manufacturing expansion for nearly three years

Growth of the U.S. manufacturing sector slowed to its weakest pace in nearly three years in July, according to the Markit U.S. Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index. At 51.4, down from the flash estimate of 51.8 and below June’s reading of 52.5, the PMI hit a 34-month low and signalled only a modest expansion during the month.

The volume of new orders received by manufacturers increased in July. The increase in total new work largely came from the domestic market, however, as new export orders fell for the second consecutive month, partly reflecting the ongoing economic crisis in Europe. Overall, new orders (both domestic and exports) rose only modestly, with the rate of increase weaker than the earlier flash estimate and the second-slowest since orders began rising almost three years ago.

Commenting on the final PMI data, Chris Williamson, Chief Economist at Markit said: “The final reading of Markit’s U.S. Manufacturing PMI was even weaker than the flash estimate, indicating that manufacturers are currently reporting the weakest growth since September 2009.

“Producers are being hit by the ongoing euro zone crisis, slower global economic growth and increasing unease about demand in the home market as elections loom closer and uncertainty hangs over fiscal and monetary policies.“With order books barely growing in July as export orders fell for the second month in a row, the survey signals a real risk of manufacturing production falling in the third quarter unless demand picks up soon.

Brazil

Further declines in both output and new orders in Brazilian Manufacturing in July

July data signalled a further deterioration in manufacturing business conditions in Brazil, with survey respondents largely citing weak client demand. Both output and new orders fell for the fourth month running, albeit at slightly weaker rates than those registered in June, and firms reduced their workforces to the greatest extent in three years.

Commenting on the Brazil Manufacturing PM survey, Andre Loes, Chief Economist, Brazil at HSBC said:

“The HSBC Manufacturing PMI stabilized in July, rising from 48.5 last month to 48.7. On the whole, the headline index and its key components remained below the 50 threshold, suggesting that the industrial sector in Brazil continued to contract in July. But at least this decline in economic activity appears to be losing momentum, with the very modest rise in the headline PMI index being led by improvements in both the output and new orders indices.”

This post first appeared on my Roubini Global Economonitor Blog "Don't Shoot The Messenger".

.png)